The boss of networking giant Cisco has said the shortage of computer chips is set to last for most of this year.

Many firms have seen production delayed because of a lack of semiconductors, triggered by the Covid pandemic and exacerbated by other factors.

Cisco chief Chuck Robbins told the BBC: "We think we've got another six months to get through the short term.

"The providers are building out more capacity. And that'll get better and better over the next 12 to 18 months."

That expansion of capacity will be crucial as advances in technology - including 5G, cloud computing, the internet of things and artificial intelligence - drive a big increase in demand.

Mr Robbins is the latest tech boss to weigh in on the debate - and with 85% of internet traffic using Cisco's systems, his opinion matters.

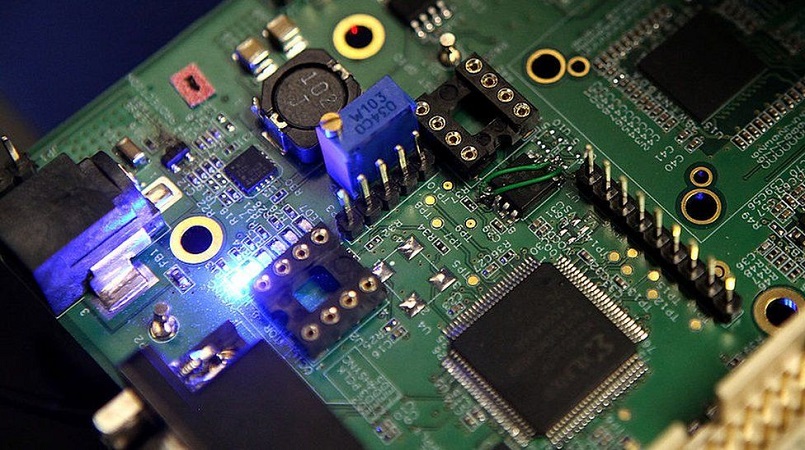

"Right now, it is a big problem," he says, "because semiconductors go in virtually everything."

The seemingly insatiable demand is why major US manufacturer Intel announced a $20bn (£14.5bn) plan to significantly expand production, including two new plants in Arizona.

According to Dan Ives, a tech analyst at investment firm Wedbush Securities, current "demand is probably 25% higher than anyone would have expected".

Even though the shortage "is going to be an issue for the next three to six months", technology share prices are doing well because investors are focused on the growing long-term demand for their products.

US President Joe Biden also sees this as a long-term issue and used a White House summit with business leaders this month to urge them to make the country a world leader in computer chips. Amid the trade and technology war with China, the White House says it is "a top and immediate priority".

The US-based Semiconductor Industry Association says 75% of global manufacturing capacity is in East Asia. Taiwan's TSMC and South Korea's Samsung are the dominant players.

European politicians also want more chips made locally, a view partly driven by concerns over China's desire to achieve reunification with Taiwan. Meanwhile, China has seen a huge growth in domestic demand for chips to power new technology, but has only a small share of global manufacturing capacity.

Mr Robbins says: "I think that it doesn't necessarily matter where they're made, as long as you have multiple sources."