Everybody is talking about it: fake news.

US President Donald Trump decries it every time he sees a critical article, the Pope has condemned it and governments are fretting about its influence, holding parliamentary hearings.

And now Malaysia has passed a law criminalising it, with a penalty of up to six years in jail. Yet no-one has defined what it is.

The term first came to prominence during the 2016 US presidential election campaign. But the problem of deliberately falsified news articles, masquerading as properly-researched journalism, goes back centuries.

However, the Malaysian government's definition in the recently-passed law is far more sweeping than that.

It has criminalised the dissemination of "any news, information, data and reports, which is or are wholly or partly false, whether in the form of features, visuals or audio recordings or in any other form capable of suggesting words or ideas”.

Human rights groups have been quick to point out that this could be used against anyone who makes an error in their reporting or social media posts.

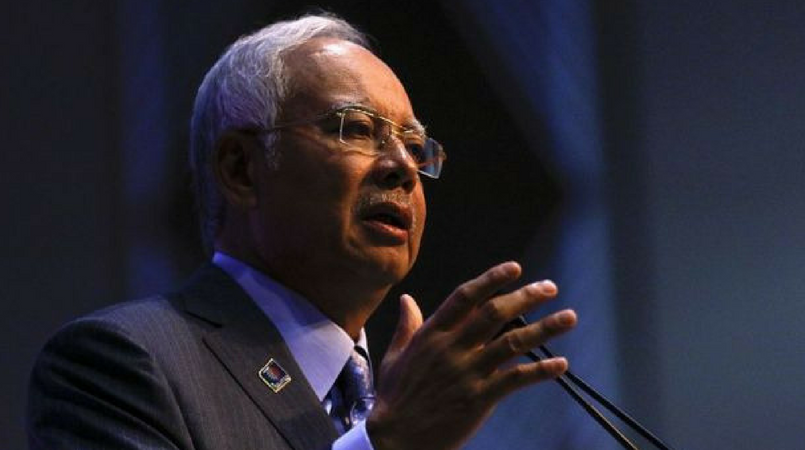

Moreover, at least one member of the government has already stated that, when it comes to articles critical of Prime Minister Najib Razak, especially over the notorious 1MDB scandal, where billions of dollars of a government-run investment board are alleged to have been misappropriated, any information not verified as true by the government will be viewed as fake news.

The fact that this law has been rushed through right before what is likely to be a hard-fought general election has raised suspicions that its real purpose is to intimidate government critics.

It is not clear anyway that Malaysia has a serious fake news problem.

In a response to the concerns expressed about the new law, the communications and multimedia minister Salleh Said Keruak highlighted the foreign media's failure to get the sometimes complicated string of official titles for high-ranking Malaysians right - irritating, yes, but hardly a threat to national security.

The article goes on to excoriate mainstream media which have published negative pieces about Mr Najib, calling them fake news, and thus rather confirming suspicions that the law is aimed at them, rather than the manipulation of social media opinion through fraudulent Facebook accounts and automated Twitter bots.

'Better safe than sorry'

Singapore is the other country which has raised the alarm over fake news, holding 50 hours of parliamentary hearings.

Facebook's policy director Simon Milner was publicly dressed down by the law and home affairs minister K Shanmugam over his failure to acknowledge the full extent of data taken by the data analysis company Cambridge Analytica when he testified to the British parliament earlier this year.

Academics speaking at the Singapore hearings presented an alarming scenario of disinformation campaigns launched by foreign actors bent on attacking the island state, of cyber armies in neighbouring Malaysia and Singapore working as proxies for other countries in undermining national security.

It also gave Singapore academics and officials an opportunity to snipe at the US belief in free expression, the "marketplace of ideas", which had allowed the abuse of personal data on Facebook to take place in contrast to Singapore's "better safe than sorry" belief in a more tightly regulated society.

But the actual examples of fake news which have come up during this national debate have mostly been prosaic; a hoax photo showing a collapsed roof at a housing complex, which sent officials rushing unnecessarily to the scene; and an erroneous report of a collision between two trains on the light rail transit line.

Irritating and worrying for some, for a while, but hardly likely to bring Singapore society to its knees. In any case both Singapore and Malaysia already have plenty of laws capable of penalising false, inflammatory or defamatory comment.

A poisonous tide

In the country where social media misinformation has had the most devastating impact, by contrast, there is no clamour for a fake news law.

Myanmar too has a raft of existing harsh laws sweeping enough to stifle any reporting deemed a threat to the state or society, laws which all too often have been used to jail journalists.

But these laws have been unable to prevent a poisonous tide of hate speech on social media, which has helped ignite anti-Muslim sentiment.

(Mr Najib has been at the centre of a controversy over Malaysia's state development fund – Gettyimages)