The streets and walls of Beirut are covered with art. Graffiti of all different designs adorn every surface and colors jump out, seemingly trying to escape their cool gray canvases.

This is where the Arab Ink Project was born.

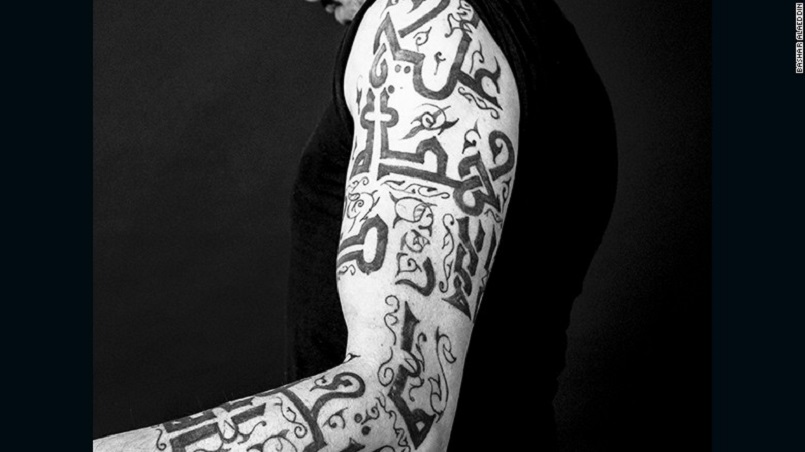

It's an initiative that explores Arabic culture through art, design and tattoos and shines a light on a culture little known beyond the Arab world -- even to people who visit the region.

The project is the brainchild of Bashar Alaeddin, who took inspiration from Beirut's graffiti as a creatively stifled freelancer back in 2013.

"I felt as a photographer to progress in my career, to fulfill my ambitions, I had to work on a very long-term documentary project," Alaeddin says. "I'd heard of these stories in National Geographic; some guy lived in the jungle for seven years or he spent time with African elephants for five years. I wanted something long term."

He had stumbled across the word "freedom" in Arabic, حرية, stenciled onto a wall in an unusual design and couldn't get it out of his head.

Obsessed with Arabic

"I was living with my mom who is Lebanese," Alaeddin recalls. "She was obsessed with the Arabic language. My whole childhood growing up it was always the Arabic language and Arabic books, all the calligraphy and different designs."

A friend of his, coincidentally, had a tattoo of the same "freedom" design done only days earlier. It wasn't traditional Arabic calligraphy and he noticed his friend wasn't alone -- a new generation of Arabs were making the language their own through tattoo art.

He thought by documenting this movement of Arabic tattoos on Arabic people and their stories behind them, he could expose this culture to a wider global audience.

"I get asked all the time what it is, even by people who do read Arabic," Hala Abdel Malak says, describing her tattoo. "It's not typical calligraphy, it reads top to down."

Originally from Lebanon, Malak lives in New York City running Design and Flow, a company focused on how design can impact society.

'Fear and division'

Her work centers on identity and symbolism so, when she met Alaeddin through a mutual friend, she was immediately drawn to the project.

"What's happening right now all over the US is fear and division," Malak says. "Unfortunately the image that we have of the Middle East and the Arab world is connected to fear."

Alaeddin's ambition for the Arab Ink Project is to try to break down these preconceptions.

"The Arab world is very diverse, it's extremely complex, but down at the heart of it we all have the same stories, we all have the same ambitions, the same meaning," Alaeddin says of the project's message.

He believes the one common thread connecting them all is the Arabic language.

"Arabic is one of the most beautiful languages. There's a lot of depth and poetry and really great expressions. As a language it's a lot more deep and sophisticated than English for example," Malak says.

"I think it's our responsibility to be able to counter all of this hatred and fear with knowledge and education and art and design. I think art is the best platform to really bring forth new ideas."

A forbidden art

This spreading of new ideas is gaining traction throughout the Arab world. Even with those who follow traditional forms of Islam for whom tattoos are considered haram, forbidden.

"Since starting the project I noticed the forbidden aspect was more of a cultural thing and not a religious thing," Alaeddin explains.

"Jordan is typically, like other Arab countries, very family orientated," he says. "[Tattoos] were looked down upon in the sense that you are just ruining the image of your body."

He says this younger generation of Arabs are rejecting that notion.

"It's an Arabic thing. Whether it's Muslim, or Christian or Jewish," Alaeddin says. "I am trying to take the whole religious aspect completely out of it. I want it to be completely about the culture. It's an Arabic generation of people with Arabic stories."

However, simply having a tattoo can still cause problems.

"I come from a very liberal family so there was never objections to having a tattoo," Professor Akram Al Deek, the Head of the English Department at American University in Madaba, explains.

Raised between Germany and Jordan, Al Deek studied and worked in England before moving back to Jordan to teach at one of the country's leading universities.

Tattoo problems

That was until his involvement in the Arab Ink Project became an issue.

"A committee was put together to question why I have a tattoo and why I have it publicly on Facebook," Al Deek says. "It was seen as a bad image to influence the students."

He left his position immediately, believing it was important not to hide his tattoos.

"I have poetry on my body and the idea is my body is mine to use and abuse," Al Deek says. "It's mine. It's not God's or anybody else's. It's mine. I'm a writer and I see myself as a canvas, as a space where I can write as well,"

He hoped his stance could encourage others to express themselves freely.

"It's very important coming from somebody who's educated and cultured. When many of my friends found out I had tattoos they immediately got a tattoo. I became sort of justification."

Battling stereotypes

It's this type of self-expression the Arab Ink Project hopes to promote, eliminating stereotypes along the way.

"By which right did you enslave people, when they were born free by their mothers?" Abed Al Razzak Samara, a financial analyst in Jordan, says translating his tattoo into English and describing its meaning.

"Everyone was born free and everyone was born human. So by which right are you judging people?"

He was drawn to the project and its efforts to combat prejudices.

"This tattoo represents for me that you have to look at people as individuals," Samara says. "However, unfortunately there are still a lot of people out there who are judging people."

Alaeddin believes, given the current tensions between borders, this is a sentiment that many will feel around the world.

Following the US Presidential elections in 2016, Marisol Razick, a middle school teacher in Virginia decided to get her second Arabic tattoo. It translates simply to "love."

'Stay positive'

Her parents, originally from what's now the Palestinian territories, moved to the United States in 1980.

"It's just a reminder that love is the answer to everything and to stay positive," she says, explaining her motivation behind the tattoo.

"When the international community think about the Middle East they think it's all about war, conflict and refugees," Alaeddin says.

"That is such a small part of a population of 400 million people. They actually have a life, have work and do go out and get tattoos. They showcase their tattoos and are willing to actually share their tattoo stories."

Alaeddin is hopeful with initiatives like his, the Arab world and the wider international community will realize we have more similarities than differences.

"You start to build your own image of a person and I want to break that down. I just want their story first," Alaeddin continues. "The Arab Ink Project is a portrait of a person with their tattoo and their story. It doesn't give you any restrictions as the viewer about how you can relate to them."